At the start of

2012, I was just beginning to develop my love for space policy. I had

joined the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary

Sciences' Federal Relations Subcommittee two years prior, but I had

played a background role. I was thrilled when I was selected by AAS

to participate in their Communicating with Washington program. My

focus: restarting production of plutonium-238 for planetary science

missions and addressing the proposed planetary science budget cuts

within NASA.

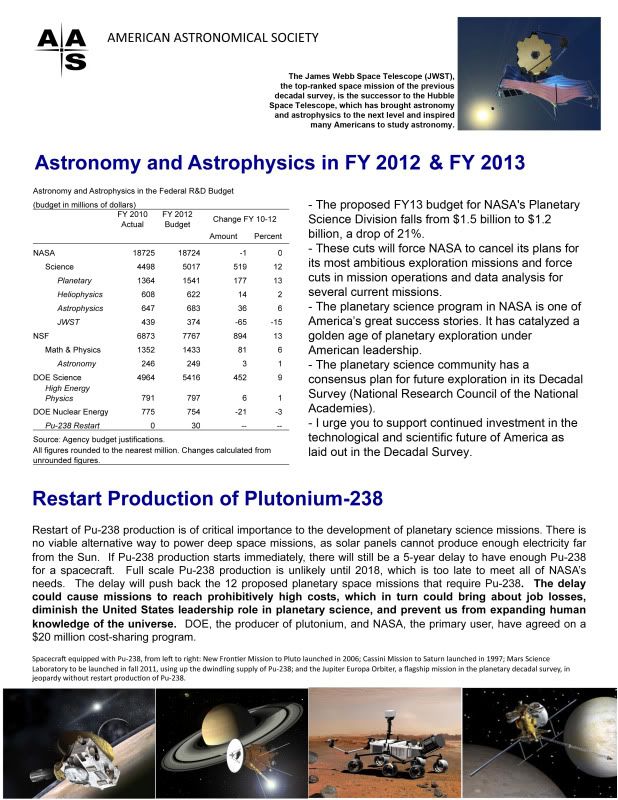

Using a combination

of AAS and DPS literature, I pieced together a flyer to give to those

I met with in our nation's capital. I thought it a shame that the DPS

FRS was dysfunctional at the time and therefore did not provide me

with any assistance or advice regarding the advocacy visit, looking

back, it may have been a good thing. I was forced to learn on my own

how to schedule and prepare for congressional visits and how to

interact with legislators and staffers. This experience helped me

tremendously with my future Tallahassee visits with Florida Space

Day, which I joined in 2013.

|

| The leave-behind flyer I made for my Washington, D.C. visit |

Pu-238, a

radioactive isotope of the chemical element plutonium, is not a

product for or from weapons. It is made from an entirely

separate process for a separate purpose, a peaceful purpose of scientific exploration. It is used as the heat source

in radioisotope thermoelectric generators which power space missions

such as Voyager 1 and 2, Cassini–Huygens to Saturn, New Horizons to

Pluto, and the Mars Science Laboratory/Curiosity. Pu-238 will also

fuel Curiosity's twin, Mars 2020.

However, Pu-238

stockpiles are very low, so low that the scarcity risks future

planetary missions. After the United States stopped making Pu-238 in

1988, we had to rely on the Russian supply, which was also running

out. In 2012, there was widespread agreement that Pu-238 production

should restart in the U.S. but there was disagreement about which

government agency should pay for it and how the supply would be

allocated.

|

| Playing tourist at the White House - March 2012 |

|

| Cherry blossom season at the tidal basin - March 2012 |

My first meeting in

Washington, D.C. was with a recent physics PhD who worked in the

Office of Management and Budget. He helped to craft the proposed

FY2013 NASA budget and thought it firm and decided. He was most interested in budget allocation

within NASA: which programs should be funded and which should be cut.

He was very interested in my graduate research and my future goals as

well.

I then met with two

members of the House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space,

and Technology, Subcommittee on Space & Aeronautics. From the

House side, the FY13 budget was very fluid compared to the OMB point

of view. Their largest priority from what I could tell was

maintaining U.S. leadership in space exploration.

|

| Fun times at the House of Representatives - March 2012 |

My meetings the

following day were Florida-specific. I met with a NASA fellow from

Senator Bill Nelson's office on loan from Kennedy Space Center. He was very concerned about the

proposed planetary science budget cuts and was curious to learn of

their extent. He seemed to want to take immediate action to reverse the negative effects of the budget cuts.

Unfortunately, my

very brief meeting with Senator Marco Rubio's office was unproductive

and the staffer I met with gave me no indication that he or the

senator cared about the issue or about NASA. Whether his stance has

changed since launching his presidential campaign, I don't know.

My favorite meeting

was with Congressman Bill Posey and his staff. Our meeting was

extensive and productive. The congressman is undoubtedly very

pro-space. Although my conversation with the congressman was

NASA-broad and we didn't delve much into specifics, my post-meeting

with a staffer in the hallway was very interesting. It was the first

of many interactions I'd have with my congressman and his office.

|

| Meeting Congressman Bill Posey - March 2012 |

My final meeting was

with Congresswoman Sandy Adams' office, whose district at the time

included Kennedy Space Center. The staffer who I met with was a

recent graduate of my university and was even aware of my specific

planetary science lab. The office was very pro-space and assured me

that the FY13 budget was being massaged.

Although NASA

received a budget cut that year in relation to the president's FY13

request, planetary science did receive a tiny budget bump up from the

initial request. Planetary science receive even more of an increase

in the following year. Although NASA's budget dropped in 2013, it's

been on a slight rise since then, though most expect the numbers to

continue to fluctuate.

Pu-238 production

was restarted to a small degree in 2013, but not nearly enough. A

series of articles have been published in the last few weeks about

the need for more for the future of NASA's planetary exploration

future. New product is expected to be available in 2019, but not as

much as the projected demand. The budgets aren't high enough for

faster or increased production.

Future planetary missions that can't rely on solar

power may be delayed, descoped, or doomed. Otherwise great science missions may be otherwise stuck in limbo without a fuel source. I can only hope that our current

legislators take a long view on the need for the Pu-238 program so that we

can continue our very successful planetary science missions well into

the future. Bring on more Mars rovers, Pluto probes, and other planetary achievements!

|

| Celebrating past space achievements and working toward future ones at the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum - March 2012 |

No comments:

Post a Comment